Cyclist

40 years of hurt: Why can’t French riders win the Tour de France?

‘Who are the French guys who can win the Tour this year? It’s a subject that’s served at the table every July,’ says Romain Bardet, whose second place in 2016 is the closest a Frenchman has come to breaking his country’s 40-year Tour de France hoodoo. Not since Bernard Hinault held off fierce rival and teammate Greg LeMond in 1985 has the home nation won the greatest prize in cycling. But why?

‘French riders not winning the Tour? Yes, it applies a degree of pressure. But it’s the same in tennis at Roland Garros. It’s something we have to put up with,’ Bardet continues. Roland Garros is the Parisian home to the French Open tennis tournament. Mary Pierce was the last French woman to win there in 2000. You’d have to go back to 1983 and Yannick Noah for the last French male.

‘These comments come mainly from people who don’t follow cycling all year round,’ Bardet says. ‘We haven’t won but we haven’t had a bad past decade or so. In 2014 we had Jean-Christophe Péraud and Thibaut Pinot on the podium. Then I finished second in 2016 and third in 2017. But people know how tight a grip Team Sky had on the race back then. It would have been a big surprise to see someone else win.’

That grip was iron-like, the British team winning seven Tours in eight years, starting with Bradley Wiggins in 2012 and concluding with Egan Bernal in 2019.

Bardet has a point when he says French riders haven’t fared as poorly as that headline stat might suggest. Still, even when battling for the podium they haven’t realistically looked close to taking the yellow jersey. In 2014, Vincenzo Nibali beat Péraud by over seven and a half minutes, while in 2016 Bardet finished just over four minutes behind Chris Froome, who wore yellow from Stage 8 onwards.

That second-tier success is reflected in the fact that France has racked up the third highest number of podium finishes in the four decades since they last won the race with nine – albeit none since Bardet finished third eight years ago. Spain is at the top of the standings with 19, but haven’t had a podium themselves since Alejandro Valverde’s third in 2015. Italy is second with 11 podium finishes, although none since Nibali’s 2014 win. Belgium, another cycling-mad nation, hasn’t won the Tour since Lucien Van Impe in 1976.

The globalisation of cycling

So winless but not toothless. There’s also an element of luck to proceedings, says experienced sports journalist François Thomazeau.

‘At the first Tour I covered in 1986 you could argue Hinault was unlucky to miss out to LeMond. And obviously there was 1989 when Laurent Fignon saw his 50-second lead eclipsed [by eight seconds] by LeMond on the last stage. Maybe I’m a jinx, as I retired in 2023 [from covering the whole Tour] having never seen a French rider win.’

Or maybe LeMond’s double triumph highlights the growing internationalisation of the Tour de France. France won the race 36 times between the inaugural Tour in 1903 and Hinault’s fifth and final triumph in 1985. On that timeline, Belgium won 18 times and Italy eight times. Over the decade that followed, Spain then took its tally from two to eight mainly thanks to Miguel Induráin’s five consecutive wins (1991-1995). LeMond’s 1986 triumph was the first by a non-European.

In short, historically the Tour has been dominated by four nations, with Switzerland and Luxembourg riding up the flanks. But since 1996 – and discounting Lance Armstrong’s redacted septet of wins – nine different countries have won the Tour, many for the first time, including Great Britain, Germany, Denmark, Australia, Colombia and Slovenia.

‘I’d say the growth of road cycling around the world is a massive factor,’ says Bardet. ‘The strength in depth from different corners of the globe just wasn’t there before.’

This globalisation of road cycling is reflected in greater sponsorship appeal around the world. According to Italian daily La Gazzetta dello Sport, UAE Team Emirates has the biggest annual budget on the WorldTour at €60 million (£52m). Next are Ineos Grenadiers and Red Bull-Bora-Hansgrohe, both at €45 million (£38m). As for the French teams, Decathlon-AG2R La Mondiale is down in seventh at €25 million (£21m) – and that’s with the boost of a recent cash injection from the global sports retailer – with Groupama-FDJ down in ninth at €20 million (£17m). Cofidis and Arkéa-B&B Hotels are 16th and 17th out of 18 with €15 million (£13m) apiece.

Despite not competing fiscally, Thomazeau says there is a contradiction here.

‘Although the French WorldTour teams don’t have the biggest budgets, historically top French riders on top French teams have been too well paid. They end up riding in their comfort zone, earning excellent wages despite mediocre results.

‘Take Bryan Coquard. I remember interviewing him for the first time at the 2012 London Olympics, where he won silver in the omnium. He was just 20 years old and had huge potential. But he’s spent his entire [13-year professional] career with French teams, wasting four seasons at a pretty poor B&B team under [team manager] Jérome Pineau. He’s now at Cofidis. Yes, he’s won plenty of times but it was often second-tier events.’

To date, the 32-year-old has won 53 times but primarily in lower-level French races including nine stage wins at Étoile de Bessèges. That said, Coquard did win Stage 4 of this year’s Tour Down Under.

‘But he could have won a lot more elsewhere,’ Thomazeau points out.

You could argue that a world-leading French performer would still be paid more at the likes of UAE Team Emirates, although arguably not for long if they underperformed. But flying the French nest just isn’t in its riders’ DNA, whether money-related or not.

France’s 36 victories at the Tour have come from 21 different cyclists, all racing for French teams, be it sponsored teams or (for the relevant editions in the mid-20th century) national teams. Bardet made ‘the brave move’, says Thomazeau, transferring from AG2R La Mondiale to Team DSM in 2021. ‘But at 30 years old it was arguably too late.’

Fighting tradition

What is it about French teams that might be holding talented French riders like Bardet back? Arguably the answer is conservatism. French cycling is deeply rooted in tradition, with former riders typically remaining at the heart of team operations a long time after they’ve retired. That, critics argue, saw France fall behind in the scientific arms race that has been modern road cycling since Team Sky came into existence back in 2010.

France has rarely been on the frontline of innovation, be it technically or strategically. Cutting-edge time-trial bikes, wind-tunnel work, sleep hygiene, nutrition ideas spawned from the lab, pacing strategies, a greater focus on quality of races not quantity… there are myriad ideas and methods that French teams have been resistant to. This is changing but there’s a definite sense of playing catch-up.

‘Team Sky came in and had so much more knowledge about training and the application of science than us. They also realised the importance of surrounding the lead rider with really strong helpers,’ says Bardet. ‘That knowledge has started to spread throughout the peloton, but back in the day it’s true that my preparation was a little more experimental than it is now. That applied to 2018 when I finished sixth. I was in the same shape as 2017 but we made some bad decisions and weren’t prepared.’

Thomazeau agrees that the adoption of sports science in France has been glacial: ‘Look at Christophe Laporte. At Cofidis he was a leadout guy, then he moves to Jumbo-Visma and he’s a changed man, winning races galore. In the past there has been an obdurate reliance on old-school training methods. It’s changing and arguably has changed, but maybe someone like Pinot would have won the Tour with another team.’

Overtaken by football

Since Hinault’s 1985 Tour triumph, France has enjoyed considerably more success in football, winning the World Cup for the first time in 1998 and adding a second title 20 years later. They also won the European Championship for the second time in 2000 (the first having come in 1984). This run of success has been built on a popularity that was once enjoyed by cycling.

‘Cycling is such a traditional sport and was number one for years, up to well into the 1950s,’ says Thomazeau. ‘Since then football has become increasingly popular, as have the likes of basketball and handball. For years, young French guys haven’t wanted to become cyclists. They’ve wanted to become the new Zidane.

‘Something that’s gone under the radar is the social background of cyclists,’ Thomazeau adds. ‘In the past, France had more working-class riders to draw on from farming stock. Hinault’s parents were farmers and he worked on their farm; Raymond Poulidor, who didn’t win the Tour but was a fine rider, grew up on a farm. It’s the same with [two-time winner] Bernard Thévenet. Even Jacques Anquetil, who had aristocratic tendencies, came from a farming background.

‘When the Americans came along, the likes of LeMond and Andy Hampsten, you suddenly had well-educated riders coming in. Nowadays it has more of a hippy air to proceedings. The likes of Guillaume Martin is even a philosopher. But French cycling struggled to make the jump from traditional rural sport into more of a university sport, which limited the reservoir you could draw on. For years it was seen as old-fashioned to be a cyclist, but the likes of Mark Cavendish, Peter Sagan and even manufacturers like Specialized have helped change that perception.’

The long shadow of doping

The common thread running through all these arguments is of a nation restrained by the manacles of history. It could be argued that French cycling was imprisoned during the dark doping days, with France arguably suffering a longer sentence than any other nation, starting with the individual but then spreading to the masses.

In 1998, the Festina team was thrown off the Tour because of the doping scandal that erupted when illegal performance-enhancers and associated paraphernalia were found in soigneur Willy Voet’s car. One of Festina’s riders, Richard Virenque, was among the favourites for GC victory after finishing second behind Jan Ullrich in 1997.

The home fans certainly felt that Virenque would have built on his 1997 performance, and there was a degree of sympathy for the French rider when it became clear that a huge percentage of the peloton was seriously doping, including the top three of Marco Pantani, Ullrich and Bobby Julich. But the Festina affair had far wider-reaching repercussions for road cycling in France as a whole.

‘Festina wiped out the 2000s for us,’ says Thomazeau. ‘There was so much scrutiny – the police were watching, the sports ministry was watching – that an entire generation of cyclists was lost.

‘Yes, there was Laurent Jalabert but I don’t think he had the means to win the GC at the Tour. [In any case, his name was on the list of doping tests published by the French Senate in 2013 that had been collected during the 1998 Tour and found positive for EPO when retested in 2004.] Ultimately, Festina killed French cycling for a generation until the likes of Pinot and Bardet came through around 15 years later.’

The implication that French riders were cleaner (and slower) during the Armstrong period – or at least not as chemically charged – is given further substance by the fact that Pinot and Bardet came to prominence after the Athlete Biological Passport was introduced to cycling in 2008.

France’s next great hope

‘Paul is a rider to keep an eye on,’ says Bardet. ‘But we mustn’t put too much pressure on him.’

‘Paul’ is 18-year-old Paul Seixas, who graduated from Decathlon-AG2R La Mondiale’s under-19 squad this winter and leapfrogged the development team to go straight into the WorldTour. In 2024 he won numerous races including the Junior Time-Trial World Championships – a discipline in which French riders are renowned for underperforming (see Race of Truth, below) – and the junior Liège-Bastogne-Liège, as well as having a string of strong performances at the recent Tour of the Alps and the Dauphiné. Could Seixas end the drought?

‘He’s certainly good,’ says Thomazeau. ‘As is Paul Magnier [21, Soudal-QuickStep] and Romain Grégoire [22, Groupama-FDJ], although I’m unsure if Romain has the profile of a Grand Tour winner. Lenny Martinez [21, Bahrain Victorious] is a good enough climber to win the Vuelta but maybe not strong enough for the Tour.

‘But back to Paul Seixas, he’s good. The problem is that there are lots of young, up-and-coming riders around the world. The previous great hope was David Gaudu. He won the Tour de l’Avenir [the prestigious under-23 race] in 2016 but unlike fellow winners Tadej Pogačar and Egan Bernal he didn’t progress and go on to win a Grand Tour. Now 28, I think that ship has sailed.

‘Will the French win the Tour in the next ten years? I’m not so sure. With guys now winning that race in their early twenties, it’s hard to predict as they’ll currently be at school. But one day we will have what Bernard Hinault calls “that guy” again, the rider who is simply a real champion, like a Pogačar or Eddy Merckx. But where that little extra something comes from remains to be seen.’

Vive la France

Four of the greatest riders in French cycling history

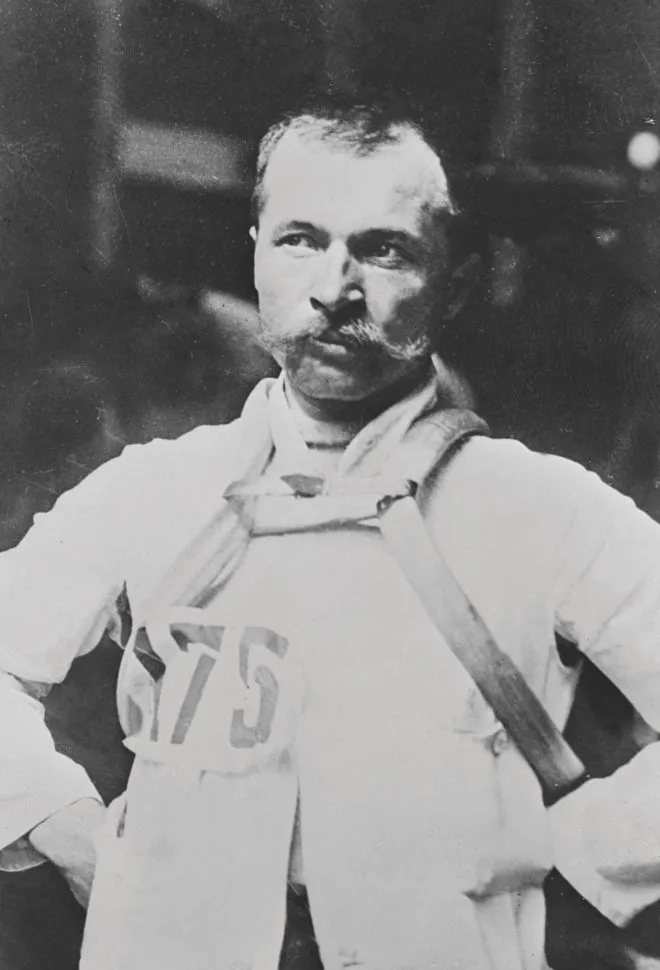

Maurice Gaurin

We’ll leave aside the inconvenient truth that Garin was actually born in Italy. All that matters is that he’d adopted French nationality in time to win the inaugural Tour de France in 1903. A former chimney sweep, Garin won three of the race’s six stages to finish nearly three hours clear of his nearest challenger in Paris. He would also win the second Tour in 1904, only to be stripped of the title months later for cheating.

Louison Bobet

A fierce rival of gifted Luxembourgish climber Charly Gaul, Bobet matched Gaul’s three Grand Tour wins in the 1950s, but unlike his rival took all three in successive years and at his home race, making him the first three-time Tour winner. After abandoning his first Tour in 1947 on the Col d’Izoard, Bobet would go on to forge much of his legacy on the same climb, winning three stages in five years after leading over the Alpine summit.

Jacques Anquetil

The first rider to win five Tours de France, Anquetil built his success on his incredible ability against the clock. ‘Monsieur Chrono’ took 11 of his 16 Tour stage wins in time-trials, and forged a legendary rivalry with countryman Raymond Poulidor, a better climber and more popular with the French public thanks to his more attacking riding style, but never a winner of cycling’s greatest race.

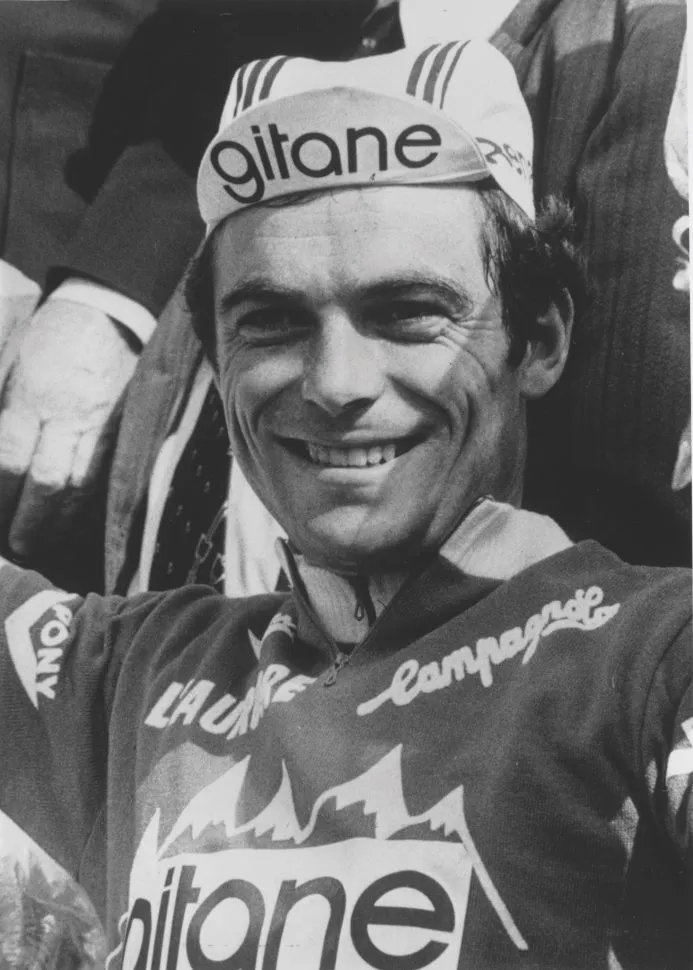

Bernard Hinault

Hinault matched Eddy Merckx and Anquetil by winning the Tour five times from 1978 to 1985, and is widely regarded as one of the greatest cyclists of the 20th century alongside Merckx. Nicknamed ‘The Badger’ for his aggressive and short-tempered manner, Hinault competed in the Tour eight times, taking a pair of second places alongside his five wins. He ranks third in the list of all-time Tour de France stage winners, with 28 wins, behind Mark Cavendish (35) and Merckx (34).

Race of truth

French GC challengers have a reputation for being poor at time-trials. Romain Bardet reveals why

‘I would say in French cycling, the feel, the hype, the enjoyment is more about attacking in the mountains. And that’s what fans, especially in the Tour de France, expect from you.

‘For me there was never a big focus on time-trialling. One of the main reasons why is that I just found it boring. It’s the opposite to what I enjoy about cycling, about going with the flow and fighting your competition side by side.

‘Still, I know that is changing and French teams are now really investing in this area. I think you will see a difference over the next few years. We have the current Junior Time-Trial World Champion in Paul Seixas, who could turn out to be the next big thing.’

The post 40 years of hurt: Why can’t French riders win the Tour de France? appeared first on Cyclist.